Many of the decisions I made about how to collect and process Twitter data were informed by ethical considerations outlined by scholars working in the field of social media data collection. I’ll briefly outline some of the general issues and concerns in this field before describing my own approaches in this study.

One of the greatest challenges in working with Twitter data is navigating the tension between the public nature of Twitter and people’s right to privacy. Twitter is a public site that makes user data openly available. In fact, when a user signs up for a Twitter account, he or she must agree to Twitter’s Terms of Service, which explicitly state:

By submitting, posting or displaying Content on or through the Services, you grant us a worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free license (with the right to sublicense) to use, copy, reproduce, process, adapt, modify, publish, transmit, display and distribute such Content in any and all media or distribution methods (now known or later developed). This license authorizes us to make your Content available to the rest of the world and to let others do the same.

-“Your Rights and Grant of Rights in the Content,” in Twitter Terms of Service (Effective: May 25, 2018). See https://twitter.com/en/tos.

The broad terms of this agreement have led a number of individuals to proclaim that the reproduction of any content published on Twitter is ethically sound. Writing in 2014, for instance, Hamilton Nolan states:

Because Twitter is public, and published on the internet, it is possible that someone will quote something that you said on Twitter in a news story. …Just because you wish that someone would not quote something that you said in public does not mean that that person does not have the right to quote something that you said in public. When we choose to say something in public, we choose to broadcast it to the world.

-Hamilton Nolan, “Twitter is Public,” Gawker (March 2014). See https://gawker.com/twitter-is-public-1543016594.

From a legal standpoint, Nolan is correct, and tweets may technically be reproduced in research and news articles under the “fair use” clause.

Yet the ethical – rather than the legal – considerations of republishing a post on Twitter or of conducting research on Twitter data is much more complex, as studies by the Digital Wildfire project team and others have shown. While there is currently no consent among academic researchers about what constitutes good practices in the study of social media data, there is a growing awareness of the issues and complications arising from the analysis of social media data in academic research. Describing these complexities, Matthew L. Williams writes:

Online information is often only intended for a specific networked public made up of peers, a support network, or a specific community. It is not necessarily for the internet public at large, and certainly not for publics beyond the internet. When information flows out of the context it was intended for, it is viewed by unintended audiences and has the potential to cause harm. Academic and regulatory delineations of the public-private divide may not hold in online contexts, and, as such, privacy is a concept that must include a consideration of expectations and consensus within context.

-Matthew L. Williams, “Data Journalism and the Ethics of Publishing Twitter Data,” Data Journalism (Feb. 2018).

Williams’ emphasis upon user intent, privacy, and potential consequences of ignoring context accord well with the four primary considerations that scholars have discussed in relation to social media research ethics: 1.) respecting user privacy and intent, 2.) obtaining informed consent, 3.) minimizing potential harm, and 4.) (potentially) anonymizing data for user protection. This fourth point is particularly tricky when working with Twitter data, not least because Twitter itself requires that any tweet that is reproduced “[s]how the user’s full name, @username, Tweet text, and profile picture, …and use the full text of the tweet” (“Display Requirements: Tweets,” Twitter Developer Terms, Active Aug. 2019). While this requirement does protect user attribution, it can nonetheless cause potential issues if a researcher is trying to quote a tweet with sensitive information that could potentially cause harm to the tweeter. It is not my intention here to analyze or contest these issues; rather, I mention these complexities in order to describe the ethical considerations that informed the data collection and analysis of Project TwitLit, which I’ll describe in more detail below.

__________

Considerations of user privacy and intent will naturally vary based on the research questions being asked and the group on Twitter selected for study. My particular project analyzes the writing community on Twitter, and some of the driving questions behind my research are: What does the writing community look like on Twitter? How has this community developed and changed over time? Are people using Twitter as a publication platform, and if so, how do they disseminate their work? What are the networks and circulation patterns of Twitter literature and Twitter writing communities?

Perhaps the most common method of trying to determine the circulation and networks of Twitter groups is through the analysis of the number of followers an individual has or else the number of retweets and likes that a given tweet receives. But this approach is problematic in that it tends to trace the networks of popular individuals or high-impact tweets, neglecting the majority of the Twitter user base. So rather than trying to gain an understanding of the literary network on Twitter through the number of likes or retweets that a given post had, I decided to use literary hashtags as a means of understanding the active literary community on Twitter. Hashtags are one of the primary means by which individuals on Twitter find a literary community and disseminate their work. On their page, “How to Use Hashtags,” Twitter writes, “People use the hashtag symbol (#) before a relevant keyword or phrase in their tweet to categorize those Tweets and help them show more easily in Twitter search.” Searchability is, in fact, one of the key features of hashtags and one of the primary reasons for using them. In “What Is a Hashtag on Twitter?”, Daniel Nations writes: “Twitter users put hashtags in their tweets to categorize them in a way that makes it easy for other users to find and follow tweets about a specific topic or theme.” Given this, hashtags are a way of indicating public and community engagement, and they have the added benefit of marking a tweet as intended to reach a larger audience than the user’s friend-base.

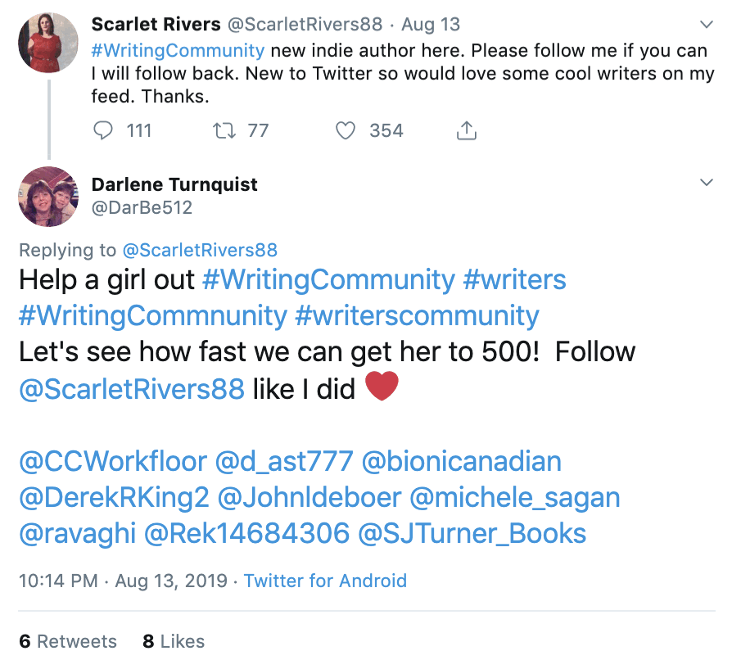

The openness and inclusive nature of the Twitter writing community became apparent as I began collecting data. For instance, on August 13, 2019, one of the self-proclaimed members of the writing community on Twitter, Scarlet Rivers, used #writingcommunity to announce her launch on Twitter and ask for more followers (see Image 1). A few days later, this tweet had received 77 retweets and 353 likes. The nature of these retweets is equally telling of the Twitter writing community: Darlene Turnquist, another writer within the Twitter writing community, retweeted Rivers’s post to multiple writing communities, including #writers and #writerscommunity, with the message: “Let’s see how fast we can get her to 500!” (see Image 2). Within 24 hours, Rivers had over 640 Twitter followers, and within two weeks, this number had increased to over 1,500. Examples like this indicated that the writing community on Twitter intentionally seeks a more diverse audience than that of their personal friends and acquaintances, and concerns with unintended people reading such tweets seems to be relatively low.

Image 1: Tweet by Scarlet Rivers.

Image 2: Tweet by Darlene Turnquist

in response to Scarlet Rivers.

Yet even though the amateur writing community on Twitter may signal its willingness and intentions to engage with a broader community than its immediate friend base through the (often liberal) use of hashtags, I also sought to obtain user consent before directly quoting a tweet, and the few tweets that I do directly quote are done so with the consent of the authors. Given, as mentioned above, the low-risk posed by this data set, I gave the Twitter authors the ability to opt-out of being quoted, as per the approach suggested by Matthew L. Williams. Twitter does not allow private messages to be exchanged between individuals who are not mutual friends on Twitter, so to contact the Twitter users, I posted a tweet in response to the message I wanted to quote. This post read:

Hi, I’m a researcher studying the writing community on Twitter. I would like to use this Tweet in a publication. You will receive full attribution. Please see https://bit.ly/33OGzjQ for more info & to contact me with questions. If you don’t wish to be quoted, please reply NO.

I allowed a two-week response period to my message. The responses that I did receive were all enthusiastic, and no one opted out of having their tweet quoted. In short, the dataset with which I am working poses low-risks of harm in that most of the tweets directed to the literary community on Twitter have little if any sensitive information. While some literary tweets are overtly political, I have chosen to not quote any of those here.

Perhaps the thorniest ethical consideration that I faced with data collection was in the form of deleted tweets or Twitter accounts, which clearly signals an author’s intent to no longer have a tweet be public. This issue is partly mitigated by the Twitter scraper I used, which does not collect data from deleted tweets or Twitter accounts. While I firmly hold that this information should be preserved for the purposes of academic research, the user’s intent should also be respected. I therefore propose that a deleted tweet should never be quoted, but it can nonetheless be used within aggregated data sets and to help understand trends. In short, unless given permission to quote a tweet, it seems that aggregating the data and presenting it in the form of graphs that represent trends in the Twitter writing community also helps preserve the privacy of individual Twitter users.